29 July 2023

10:12-10:36

I’ve taken the window seat again but the view is completely blocked by a full-scale adhesive on which I can see, to the left hand side, half of an enormous iced Americano in a plastic cup turned upside down. A strip of classic Pret dark red runs parallel with the bench on which I’m resting my notepad, and on this strip I can read the words backwards: DERAPERP YLHSERF [Pret Star] TAL. TAL, or LAT would spell LATTE, were the strip allowed to continue instead of ending where the window meets the wall.

£6.40 for 500ml still water and four eggs on beds of spinach, two per plastic tub, aka Egg & Spinach Protein Pots. (The salt sachets are free. In Five Guys, the roasted peanuts in their shells are free.) Two for now (a second breakfast after a smoothie I made on waking up), two for lunch – I’ll take them in my bag to the British Library where I’ll continue to read Onward, along with Ann Vickery’s Leaving Lines of Gender.

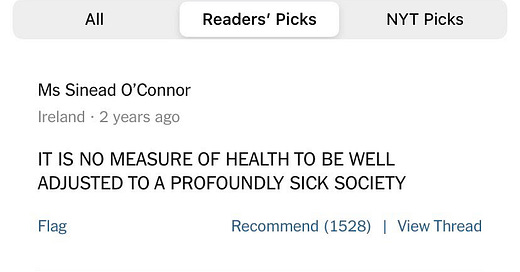

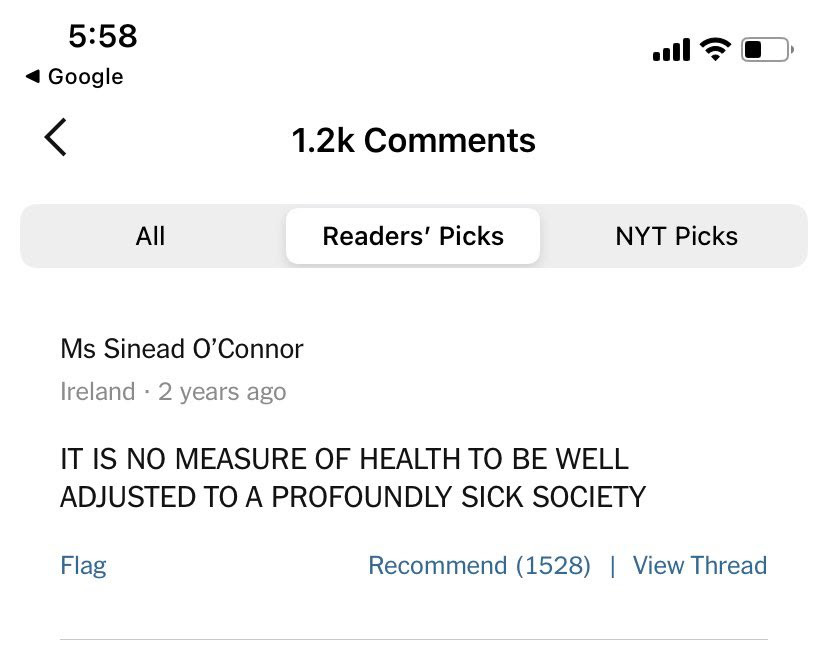

I’m eating eggs because, as detailed in this REPORT, I was in hospital last year and due to a combination of olanzapine, sedentariness, and hospital food, I put on weight. ‘I’ve started to care less’, I wrote in April, but the cares lessen then they regrow. I sometimes feel uncomfortably different from how I used to be. My therapist suggested I was concerned with the idea of waste: a sense of physical excess, wasting time, (fearing) wasting my life. A friend with an eating disorder once suggested to me that it was perfectly possible to be healthy regardless of weight, high or low. Since Shuhada' Sadaqat/Sinéad O’Connor’s recent death, many people have been quoting the comment she made on her New York Times profile, ‘IT IS NO MEASURE OF HEALTH TO BE WELL ADJUSTED TO A PROFOUNDLY SICK SOCIETY.’

Hunger and dieting may be consonant with misery. Hunger has a relation to desire.

In the introduction to Studying Hunger Journals*, Bernadette Mayer writes:

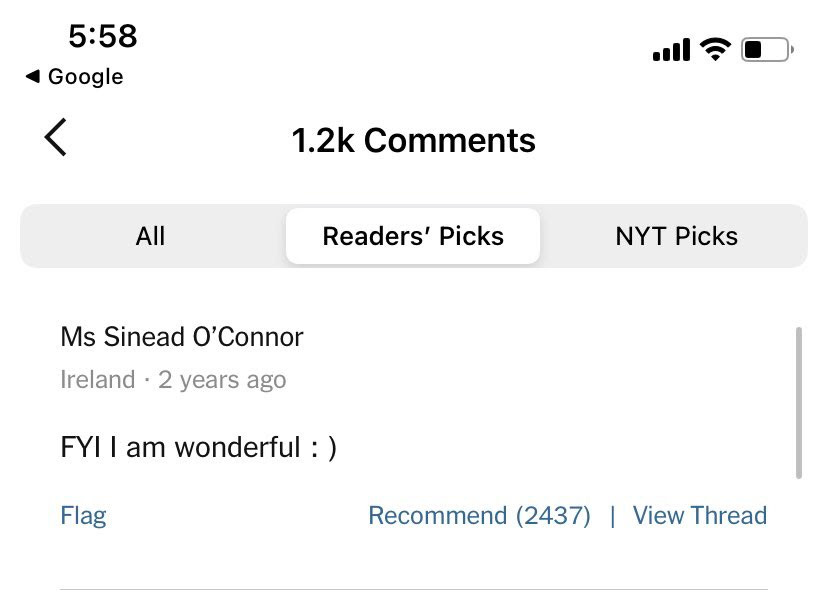

The “hunger” in the title comes from regular hunger which I felt in the extreme because my parents had died young (there was nobody to feed me) & from a concept delineated in a line from a poem I wrote then: eating the colors of a lineup of words. You know how people say they “devoured” a book? The synaesthesia I experienced made the letters & words seem as edible as paintings.One of the symptoms I experienced was that I couldn’t swallow, perhaps as in “I couldn’t swallow it.” For more about this phenomenon, read Freud’s case of Anna O.

…

It may seem odd that both books, MEMORY and STUDYING HUNGER, were published in the same year or that I embarked on STUDYING HUNGER right after doing MEMORY but I was in a great hurry. I figured I’d die like my father did, at age 49. I did have a cerebral hemorrhage at that age just like him but I didn’t die, I had brain surgery & lived to eat more oysters.

On page 140 of Studying Hunger Journals: ‘Making love has always been the solution to the problem of my hunger for people. What other way is there?’

…

According to Michael Ruby, someone should ‘pore through’ Mayer’s Memory looking for references to the work of poet and close friend of Mayer’s Hannah Weiner. It was after completing Memory (a one-month shoot of thirty-six pictures per day and an accompanying tape recorded and transcribed journal, July 1971) that Mayer began Studying Hunger Journals – a series of books swapped with the psychiatrist she began seeing when on the verge of feeling mad.

Hannah Weiner wrote The Fast (1992) at the end of 1970, following a twenty-one day fast into which Bernadette Mayer intervened. Michael Ruby is ‘tempted to say that fasting was a fad that reached the suburbs of New York, where [he] was growing up, precisely in 1972, appealing to people both as a natural high and as a way of purging the body of the unhealthy chemicals in the American food chain.’

The Fast is in the British Library, I have ordered it for Thursday. Meanwhile, as well as the pdf of Weiner’s Clairvoyant Journal (1974), I’ve found these readings and these publications online. In Translating the Unspeakable (2000), Kathleen Fraser writes:

Seemingly incoherent – yet “known language,” in which the absence of traditional grammatical representation is given visual body – entirely fills the field of the mind/page, in Hannah Weiner’s Clairvoyant Journal, whose jacket features a photo of Weiner's forehead painted with the message I SEE WORDS. The word density encountered by the reader is an actual projected simulation of Weiner's multiple language tracks, activated by a trauma in the late Sixties, after which she began to “SEE WORDS,” writ LARGE, on other people’s bodies or on surfaces of walls and buildings. What might have been dismissed or narrowly defined as a “psychotic break” by others became for Weiner (already a poet interested in the visual), new material for poems. Conceiving of her page as a screen, she projected in upper- and lowercase “dictation” the speaking voices and seen WORDS appearing from both inside and outside her psyche. In this way she was able to communicate a distressed and chaotic state – with a good deal of humour – as well as constructing a meaningful written artifact containing within it a visualized performance of her daily condition.

I want to compare the way Mayer considered letters and words as ingestible – existing outside then inside her body – with the way for Weiner words were both ‘inside and outside her psyche’.

A page from Mayer’s Proper Name (1996) which indicates the colours of ingestible letters.

In Mayer’s ‘The Way to Keep Going in Antarctica’ (1968), ‘Nothing outside can cure you but everything's outside’. There’s the phrase ‘everything but the kitchen sink’ and both Michael Ruby and Johanna Drucker, the latter reviewing Weiner’s The Fast in The Poetry Project Newsletter October/November 1992, Volume #146, write about the sink in The Fast. For Drucker, it is important to begin her review by noting that Weiner ‘ended up spending most of three weeks [...] “in the kitchen sink”, with the sink supposedly synonymous with a rite of purification.** A repeated refrain in Mayer’s work concerns a problem of everything or nothing: in Midwinter Day (1982), ‘How preoccupying / Is the wish to include all or to leave all out / Some say either wish is against a poem or art / I’m asking / Is it an insane wish?’ (p. 102) And Mayer describes Memory ‘as a piece, to mesmerize, to suck you in to leave all out to include all’.

Teleportation involves becoming nothing (dematerialising) in order to become all (to rematerialise) again. I’ve otherwise departed quite a bit from teleportation and the notes I wrote by hand in Pret. Those notes continue: It is a shame to turn eating into a preoccupation…

…

My friends tell me their relationship to food routines and diet fads: prescription-based shakes; only white things (this documentary says that ‘white is not Marxist’); thirty different plants each week, including spices. I once read a student newspaper article in which the writer ate one different colour of food per day for a week.

Several people (I forget who, on Twitter) have commented on the hatred of fatness in Otessa Moshfegh’s novels. I’ve only read My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018) in which the protagonist watches with fascinated contempt as her only friend Reva eats and drinks.

I remember watching the Joan Didion documentary and how she talked about surviving on Diet Coke and almonds. She looked increasingly bird-like and papery as she aged.

I recently read ‘THE “UNHINGED BISEXUAL WOMAN” NOVEL’ book review article, by Emma Copley Eisenberg, in which ‘Greta is fascinated with and repulsed by people who actually eat meals, chief among them the woman she wants to have sex with.’ More in tune with my politics is taking pleasure in the body, and in food. Think of the way fat carries flavour, and how Audre Lorde in ‘Uses of the Erotic’ (1978) describes the margarine:

I like Jules Gleeson’s tweets about the body and want to be her aesthetic comrade:

12:51

I was too hungry to eat only two eggs for lunch so after drinking a green tea from the British Library entrance Origins pop-up, I got a TANPOPO sweet chili tuna onigiri from the first floor cafe. It costs a bomb to study here if you don’t bring a packed lunch. During my MA I would work at Senate House Library and get a free lunch of rice, dhal and cake from the Hare Krishnas. Of course, if you’re paying for food near the British Library, Pret, King’s Cafe on Phoenix Road and Thenga Cafe on Cromer St are better value, but I didn’t want to leave the building.

14:14

A can of Diet Coke.

In her Writing Experiments Bernadette Mayer suggests keeping journals of food.

18:36

Wong Kei soy chicken noodle soup.

In all my visits to Pret I have still never been given anything for free. I met Kat at the ICA and she told me how at 18:00 she had been at Pret 48 Bernard St, the one opposite Russell Square tube station, which has a Roger Fry blue plaque on its wall. She’d been buying chicken soup and was given a free peppermint tea and Cinnamon Danish. The Pret worker suggested ‘Sometimes these help.’ It had been a while since Kat had been given free things in Pret, and she’d been worried she’d lost her touch.

Kat’s hands and a tray of free Pret food and drink.

On 18 November 2018, the day of the first teleportation walk, we could hardly believe it. At our meeting point, Pret, UNIT 13 (RT3) Canary Wharf, Kat was given a whole tray of food gratis: macaroni cheese, a soup, and a hot drink. On arrival at Jupiter Woods we refuelled with pizzas bought en route and watched the film Love & Teleportation (2013).

A picture from the TfL ferry from Canary Wharf to the other side of the river, 18 November 2018. From here we walked to Jupiter Woods.

23:23

A glass of the best (Krasnystaw) kefir and a chunk of cheddar cheese.

*begun in 1972, part of Studying Hunger Journals was published as Studying Hunger in 1975; then published as a complete manuscript in 2011 by Station Hill Press, having been turned down by Sun & Moon in 1985, ‘on the grounds that it was a long work and there was not a large enough audience for journals at that particular moment’. (Vickery, p. 156)

**Thanks to Kay Gabriel for sending me a pdf of the newsletter this review appears in, along with a review of The Bernadette Mayer Reader (1992) by Peter Gizzi, and an interview with Mayer by Ken Jordan.